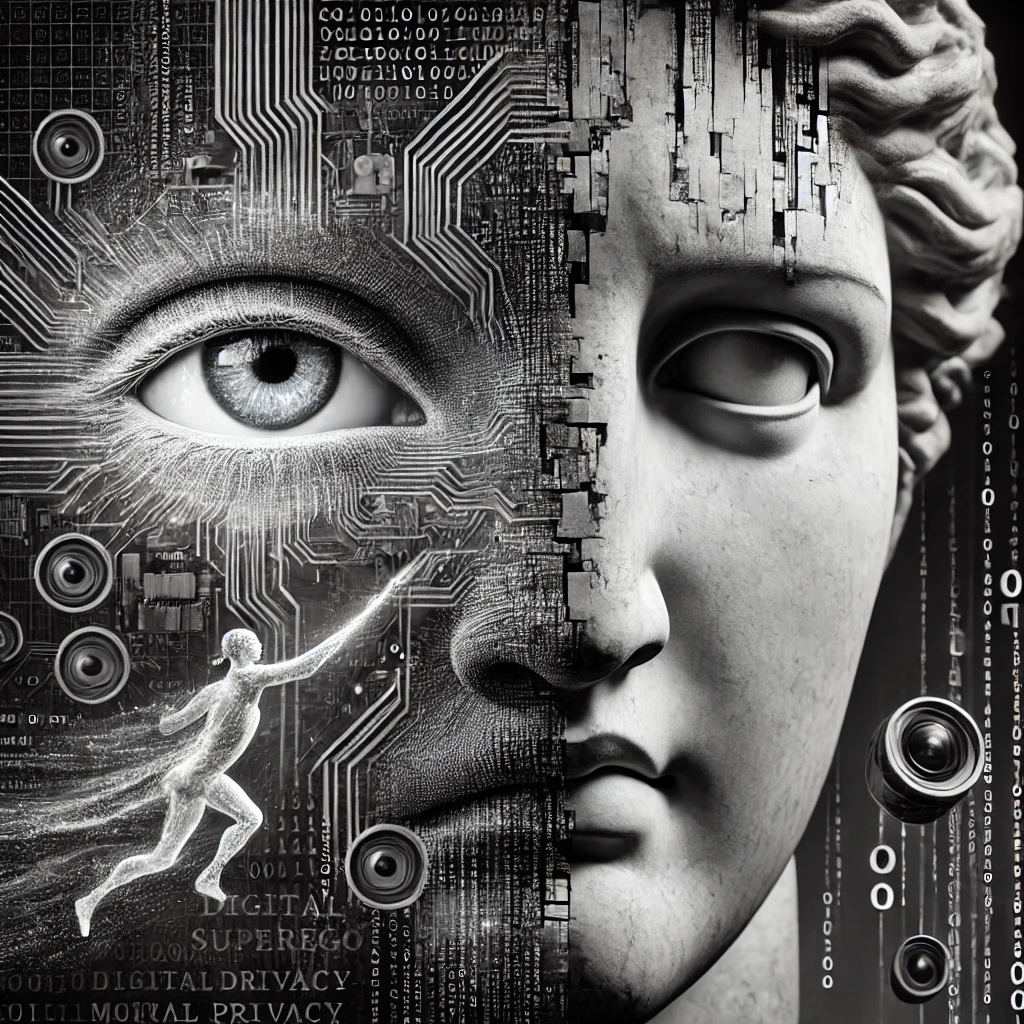

Digital and social media in particular have redefined, as we often write and even more often experience in person, the boundaries between public and private, recombining traditionally separate areas of our lives in new ways. In the past, it was traditionally only public figures and artists who could afford to mix public and private life at will, not infrequently arousing scandal for this very reason. Now we can all be writers of posts, artists of images and videos, in which we publicly display our private lives, which are therefore no longer private, but which we only wish to make public at the times, in the ways and in the quantity that suits us. We are therefore the new stars and, like good stars, we fear the paparazzi, while forgetting that we are our own paparazzi. (Castigliego G., n.d.)

It is precisely in the light of this conflict between the narcissistic desire to show ourselves to others and the desire to protect ourselves from the enquiring gaze of others, as old as human beings but redefined in new forms by the digital, that I think it is useful to interpret the data from the observatory on privacy and security.

As Prof. Epifani writes, “in a context in which the digital society is increasingly based on the extensive use of personal data – also to feed artificial intelligence systems – the general awareness of the importance of data protection is often lower than its actual relevance. This perception gap is not uniform across the territory, but shows significant differences between large urban centres and very small municipalities, making a deeper analysis of local dynamics necessary.”

The Boundaries of Ego and the Perceptual Privacy Gap

The survey shows a gap between the awareness of the importance of privacy and the real perception of its impact. Of the total, 51% believe that technology will require a rethinking of privacy, but only 25% are firmly convinced. In the Large Centres, there is greater confidence, with 30% convinced of a need to redefine privacy and only 20% sceptical, while in the Small Centres, the data reflect a less defined perception, with 29% believing the impact to be ‘little or not at all’ and only 19% expressing conviction.

This reflects a psychoanalytic dynamic related to what Freud called the boundaries of the ego, redefined precisely by the digital. Indeed, Freud (Freud, 2007) describes the ego as a structure that mediates between the internal and external worlds, establishing boundaries to protect the individual. In social psychology, too, the boundaries of the ego indicate the limits that allow us to define ourselves as individuals and to separate ourselves from others and from the social pressure to which we are subjected. Freud himself had also emphasised that such ego boundaries should not be understood as permanently defined geographical frontiers but rather as variable limits to be rendered graphically ‘through shaded fields of colour as in modern painting’ (Freud, 2013). Digital privacy can be seen as a modern extension of these boundaries: protecting one’s data, communications and identity online is equivalent to defending the integrity of the ego from external intrusions (companies, governments, hackers, social networks).

In large urban centres, interaction with the digital is more intense and the boundary between the self and the outside world (others, platforms, institutions) is more exposed and constantly redefined. In small centres, on the other hand, the relationship with technology is less pervasive and thus the need for protection of the ego boundary appears less urgent. This would also explain the greater reliance on state regulation in small towns, where the sense of personal control over one’s digital identity is less developed.

The Big Other and the power of social networks

The survey also shows that 52% of respondents believe that social networks have a ‘fairly’ strong influence on people’s behaviour, with 23% considering this influence to be ‘very’ pervasive. In the Large Centres, there is the highest level of concern, with 31% of respondents believing that social has ‘very’ and 50% ‘fairly’ strong influence, with only 19% sceptical.

This may reflect greater exposure to social media in urban contexts, where digital dynamics and social behaviour are more intense and visible. In contrast, in small towns, there is more optimism: 32 per cent believe that social influences ‘little or not at all’.

This perception can be interpreted through the Lacanian concept of the Big Other (Lacan et al., 2002), which he understands as the set of symbolic and linguistic structures that influence the individual. In digital society, the Big Other can be embodied by algorithms, artificial intelligences and surveillance systems that record, interpret and predict human behaviour. The digital subject lives knowing that he or she is being watched, thus conditioning his or her identity and desires. This recalls the concept of ‘subjectivation through gazing’, where the awareness of being observed modifies our behaviour, often unconsciously.

The greater awareness of this phenomenon in large centres suggests that here the individual feels more strongly the presence of a constant and normative gaze (social media, AI, algorithmic surveillance), whereas in small centres this perception is more nuanced.

The digital superego and social judgement

The survey shows that 24% of respondents always take care not to violate the privacy of others before sharing information online, while 26% do not care at all. In small towns, the percentage of those who do not bother rises to 32%.

This could be traced back to the concept of the superego reinterpreted in a digital key. As we know, Freud introduced the concept of the Superego (Freud, 2007) to indicate the psychic instance that represents the internalisation of moral and social norms.

In the digital context, the superego can take the form of implicit norms dictated by social media, expectations of online performance and the constant judgement of others. Control and self-control arising from fear of public judgement (or algorithmic censorship) influence the construction of identity and how individuals relate to the concept of privacy.

In large centres, constant exposure to social media and social surveillance dynamics creates greater regulation of behaviour. The digital super-ego imposes an internal censorship, causing individuals to be more careful about how their actions may be perceived by others. In small towns, where digital culture is less entrenched, this social control is less strong and attention to the privacy of others is less structured.

Narcissism and the paradox of privacy

One of the most interesting data concerns the contradiction between the perceived importance of privacy and the willingness to sacrifice it for more personalised services. 66 per cent of respondents say that privacy is a priority value, but 65 per cent also agree that if a service is useful, privacy can take a back seat.

This paradox can be explained by the concept of narcissism. Originally, Freud (Freud, 2012) explored the concept of narcissism as self-love, which leads to self-enclosure, to rejecting relationships with others, especially if we feel our own needs painfully pulsating in that relationship. Whereas, however, from Greek mythology

Until the analogue era, exaggerated self-interest was expressed in the metaphor of the mirror and mirroring, as in Narcissus seeing himself reflected in water, now narcissistic mirroring occurs through social visibility, likes, the amount of followers. On the one hand, privacy is seen as a defence of the ego, on the other, the need for visibility, recognition and digital comfort drives many to compromise in a constant negotiation between exposure and protection.

Aaron Balick (Balick, 2014) has explored the topic of narcissism in the digital age in depth, analysing how online platforms influence identity construction and self-perception. According to Balick, social media act as digital mirrors, reflecting edited versions of ourselves that can distort our perception of authentic identity. However, as we seek connection and recognition online, we also expose our frailties, making us vulnerable to external judgements and influences. Balick’s reflections help us understand how, in the digital age, we are constantly constructing a public image of ourselves, both online and offline. This process is natural and partly necessary: it allows us to present a socially acceptable version of ourselves to others and to protect the most intimate aspects of our personality.

However, as Balick (2014) warns, the real risk is not that others confuse this image with our authentic identity, but that we ourselves believe it. This happens when the individual identifies completely with their digital profile, forgetting that it is only a partial representation of themselves.

This concept is related to Donald Winnicott’s (Winnicott, n.d.) theory on the false self, which develops when a person, in order to adapt to external expectations, constructs an identity that no longer reflects his or her authentic needs. In the digital dimension, the false self becomes problematic when the subject begins to live only through their account, losing contact with their authentic identity, the more spontaneous and creative one. In these cases, the false self is no longer a simple means of mediating with the world, but becomes a rigid mask that suffocates the real self, making it difficult to have an authentic experience of one’s individuality.

The contradiction such that 66% of respondents say that privacy is a priority value, but 65% also agree that if a service is useful, privacy can take a back seat is the most accomplished expression of the confusion that reigns in two-thirds of us between the false and the true self.