An inventor and an entrepreneur popularised a writing instrument that we now consider trivial and obsolete compared to our touch screens. But this enabled mass schooling and the spread of culture, indispensable elements to participate in the journey towards sustainability

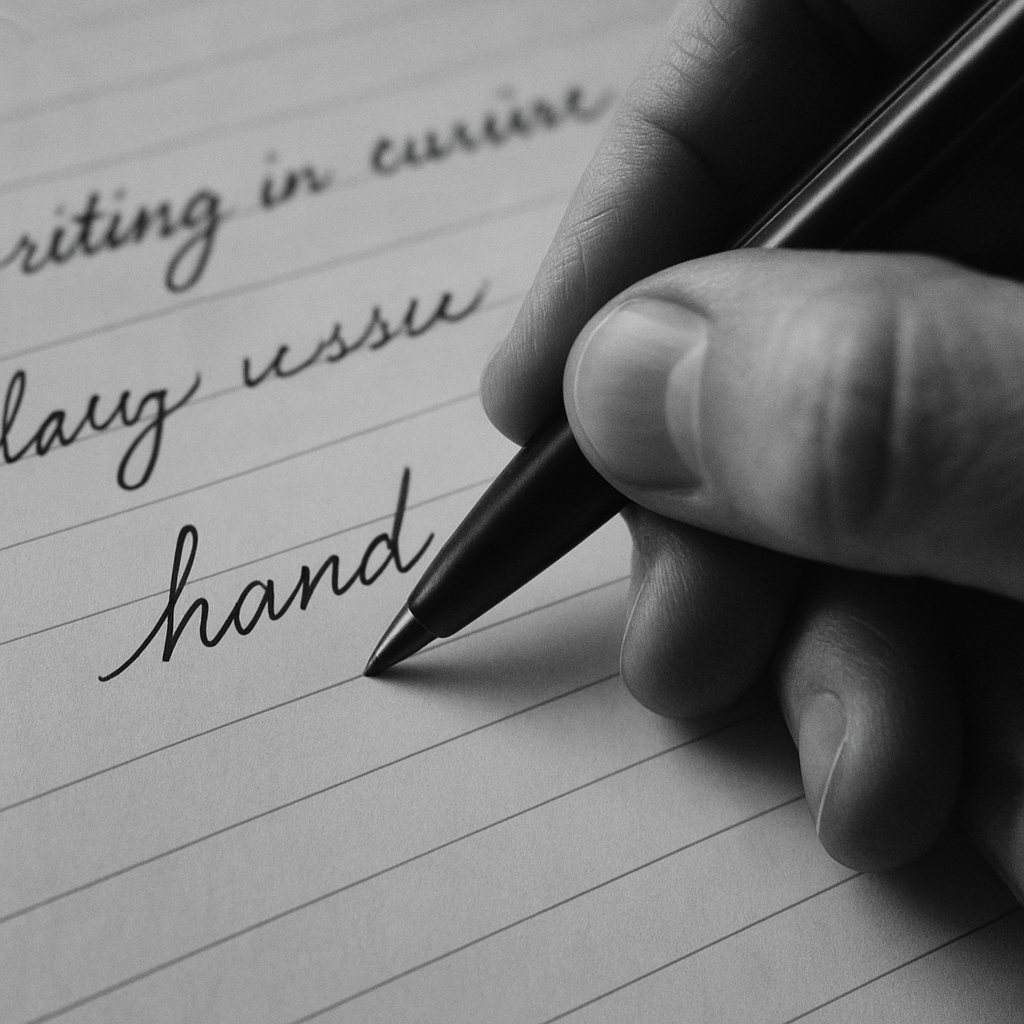

A century ago, the simple act of writing – even just taking notes – still required a certain amount of patience, skill, and a good supply of ink. Fountain pens, although elegant, had a special talent for creating disasters: ink that dripped everywhere, tips that clogged, sometimes explosive black or blue eruptions, on an important document or right in the breast pocket of the best shirt. For those who could not afford them, there was still the quill pen and inkwell, for the lucky ones a metal nib on top of a wand. And then, a contract or a thought destined to last for centuries, you certainly could not write them in pencil. After each creative venture with those tools, the hands of schoolchildren – but also of adults – seemed to have emerged from a battle against an ink-laden octopus.

It was a time when writing was not exactly synonymous with practicality, let alone popularity. Then, one day, a Hungarian journalist named László Bíró decided it was time to change the rules of the game.

László Bíró: a flash of genius

László Bíró was not only a journalist, but also an inventor. Born severely underweight, he was saved by his mother, who thought of inventing a prototype incubator on the fly by stuffing the baby into a cotton-lined shoebox and placing a lamp on top.

A survivor, a man with an inquisitive mind and a keen eye for detail, Bíró decided to become, in order, a doctor, hypnotist, painter, writer, art critic, car racer and stockbroker. After various vicissitudes, he arrived at the most difficult career: that of a journalist. He often found himself having to take notes in a hurry and even he found the fountain pens of the time to be less than ideal for the task. One day, while observing the work in the printing shop, Bíró noticed that the ink used to print newspapers dried quickly without smearing. This triggered an idea in him: why not create a pen that used a similar ink?

Bíró started working on this idea with his brother György, who was a chemist. The ink was developed, but how to apply it? You couldn’t take a printing press with you. Apparently, the inspiration came from watching children playing with glass marbles in the street. Passing through a puddle, one of them continued on its way dry, leaving a muddy trail behind it. Hmm…

Thus, the two brothers developed a pen that used a small rotating ball at the end to transfer ink from the pen to the paper. The ink, which was thick and viscous, was released evenly from the ball, avoiding smudging and drying quickly. In 1938, the two brothers obtained a patent for their invention, creating the first biros, or ‘biro’, as it was named in honour of its inventor.

This rotating ball represented a radical change in the way of writing: no more nibs dipped in ink, no more stains on the fingers. But, as is often the case with inventions, commercial success was not guaranteed. Bíró was a genius, but not a businessman, and his biros needed someone who knew how to bring it to the general public.

Baron Bich: the visionary entrepreneur

This is where Marcel Bich comes in. A French name but born in Turin and a descendant of the mayor of Aosta made a baron by King Carlo Alberto, Marcel inherited his title. He wanted to be an engineer but did not even manage to attend university. An aspiring entrepreneur, he set up a nib manufacturing company and was convinced – with good reason – that he knew an opportunity when he saw one: Baron Bich had spotted in the biros the potential for something much bigger.

After two years of work (and, to be fair, after Bíró’s original idea had been stolen) Bich put the first biros on sale.

Behold, the revolutionary Bic Cristal!

Actually, the failed engineer/inventor/entrepreneur started work on an improved and cheaper version of the pen.

First of all, Bich made the section of the casing hexagonal, allowing it to be gripped firmly and not seen rolling off the school desks, which until a few decades ago were mysteriously tilted. Then, he introduced a tiny hole in the reservoir that balanced the internal and external pressure and allowed the ink to drop evenly. He gave the ink the right viscosity and thoughtfully used transparent polystyrene to make the casing and reservoir so that the ink level could be checked at a glance.

Finally, in order to achieve an even flow of ink on the paper, he had precision instruments made for the production of the tip and ball (in nickel and brass) that guaranteed imperfections below 5 thousandths of a millimetre.

But Bich knew that to be successful, the pen had to be accessible to everyone, not just the rich or professionals. After years of refinement, he launched the ‘Bic Cristal’ in 1950, a simple, inexpensive and incredibly effective biros. With a price so low that anyone could afford it, the Bic Cristal quickly became a worldwide success: it was a pen that worked anytime, anywhere, and for everyone.

A final feature of the pen – which perhaps not even Bich himself could have imagined but which the more turbulent schoolchildren soon discovered – was that, if the back cap and reservoir were removed from the hexagonal casing, a deadly blowpipe could be obtained. This, when properly loaded with grains of rice, could turn classrooms into fearsome battlefields.

Thanks to his invention, Marcel Bich turned a small pen into a global colossus. The Bic Cristal became the world’s best-selling writing instrument, and Bich amassed a considerable fortune. But it was not just about money: the Bic Cristal had democratised writing, making it accessible to millions of people around the world.

In the meantime, Bíró, after an unspeakable series of financial misadventures, had sold the rights to his invention to the Swiss banker H.G. Martin’s Biro Patente. The latter, realising the plagiarism, had no qualms about taking the baron to court. Certain of losing, Bich left for Zurich and made a deal with the banker to settle the patent rights by paying 100 million francs in two years. In France, Belgium, Holland and Luxembourg alone, he had already made a profit of 1,200 billion francs from the marketing of the Bic Cristal…

The impact of the biros on society

Before the biros, writing was an activity that required patience, skill and, often, a lot of money. For the first time, millions of people could write with ease, without worrying about ink stains or pens that stopped working mid-sentence.

The biros not only made writing more accessible, but also contributed to the spread of written culture. Texts that were later to be printed in books, magazines and newspapers also became easier to write, promoting mass literacy and learning. Taking notes also became easier and more immediate, aiding memory, study and teaching; thus contributing to the overall growth of knowledge and culture.

The biros became an essential tool in schools, offices and homes all over the world. It was cheap, practical and reliable, and for many years represented the only means of writing available to most people.

From fire to Bic: the evolution of tools

Thinking about the great technological changes that have shaped our history, we often focus on inventions such as electricity, the combustion engine or the internet. However, tools as simple as the biros have had an equally profound impact on the way we live.

Humanity has always sought to capture and use the energy of the world around it, from the days of fire and windmills to the inventions of Leonardo da Vinci, who imagined machines to fly and tools to improve daily life. The biros is a perfect example of how a small technological change can have a huge impact on society.

Just as fire allowed humanity to evolve, the biros allowed knowledge to spread, breaking down economic and social barriers. And just as the biros democratised writing, other modern technologies can democratise access to resources and energy, making a more sustainable future possible.

A tiny tool drives a revolution

Today, as we enjoy typing on our touch screens, complaining about virtual keyboards and scanning orders to Alexa, the faithful old biros might seem outdated. But it is thanks to her that billions of people have been able to learn to write, take notes and sign contracts without having to deal with an ink stain on their shirt. She literally put the pen in the hands of the whole world. And these hands have developed brains capable of understanding and taking an active part in the sustainability challenge.

And as we think about the future, made of solar panels, electric cars and artificial intelligence, let us remember that progress often stems from small inventions like the biros, capable of changing the course of history. Because, after all, sustainability is not only built with grand gestures, but also with the small things that simplify our lives, learning and spreading ideas, just like the biros did. Who would have thought that a small glass ball rolling in the mud could write such an important piece of our history?